UH’s Venerable Ocean Time Series Enters a New Era of Leadership

At over 60 million square miles, the Pacific Ocean is the Earth’s largest and deepest ocean basin. In the middle of it all, lies a vast swirling system of currents known as the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG). At four times the size of the Amazon rainforest, it is considered the world’s largest ocean ecosystem.

However, unlike the Amazon, most of the plants and animals in the open ocean are microscopic. A single milliliter of seawater can contain more than 100,000 specimens and they come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, colors and metabolisms. Some of these microbes produce oxygen, consume carbon dioxide and form the base of the food web upon which every other form of ocean life is reliant.

HOT/Station ALOHA

Since 1988 on an almost monthly basis, a dedicated and diverse team of University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa) scientists have sailed into the NPSG, located 100 kilometers north of the island of O‘ahu, to their field site known affectionately as Station ALOHA (A Long-Term Oligotrophic Habitat Assessment). This 33-year pilgrimage has been in support of the Hawai‘i Ocean Time-series (HOT) program, one of the longest-running open ocean time-series on Earth, co-founded by world-renowned oceanographer David Karl.

“Decades of sustained ecosystem observations from HOT have revolutionized humankind’s understanding of the ecology, physics, and biochemistry of the NPSG that surrounds the Hawaiian Islands and provides some of the only decadal-scale observations to gauge future changes in the ocean,” said Karl. “The program is also a testbed for new technology and serves as an invaluable training ground that has attracted researchers from around the globe.”

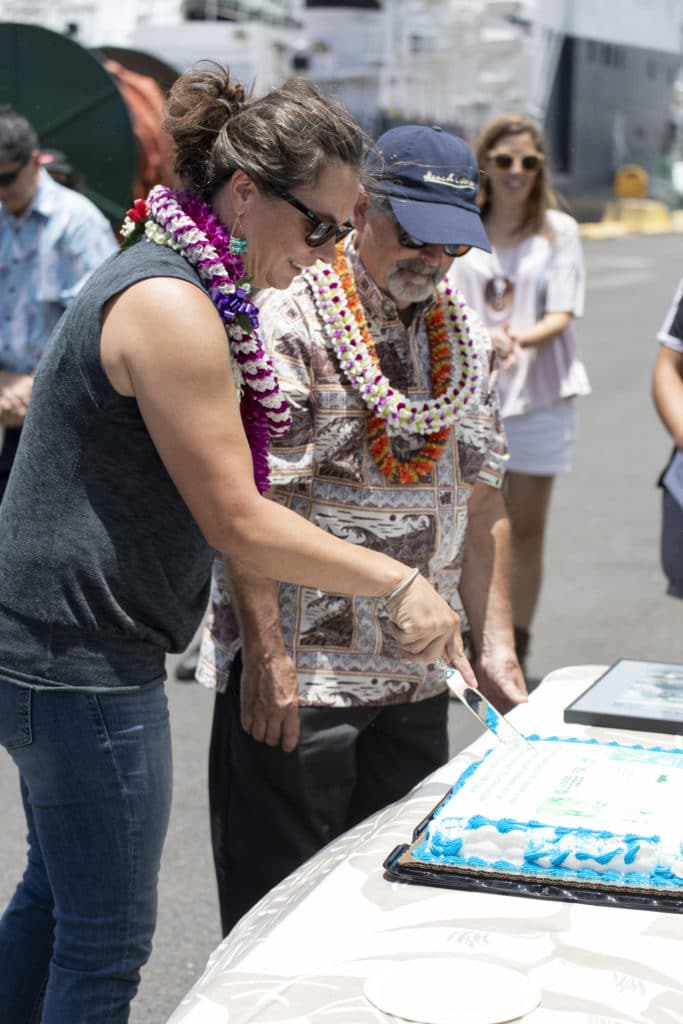

One of those researchers was Angelicque White, who took over for Karl as principal investigator of HOT in 2019.

Influential First Meeting/Early Work

White was first introduced to Karl in 2002 when she participated in a HOT cruise while working on her PhD in biological oceanography at Oregon State University (OSU), after earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology from the University of Alabama at Huntsville. In 2006, White was a student in the inaugural Agouron Institute course in microbial oceanography at UH Mānoa that was built on the scaffolding of HOT, and later became one of the course instructors in 2012. During her postdoctoral years and later as an assistant professor at OSU (between 2006-2012), she also was a part of Karl’s acclaimed Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education (C-MORE) program.

“Since then, Hawai‘i and the HOT program have been an intellectual home for me in many ways,” said White. “They were formative scientific experiences that built strong research ties and forged long-standing scientific collaborations for me with the state and UH.” White’s work focused on the study of harmful algal blooms, remote sensing of phytoplankton and ocean acidification along the Oregon Coast, that included the utilization of a 20-year time series at OSU. At the same time, White built a rich funding portfolio with support from diverse sources, including the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and private funding sources such as the Simons Foundation. Her research, teaching and outreach efforts were recognized by a research fellowship from the Sloan Foundation in 2012; and prestigious early career awards from the American Geophysical Union in 2015 and the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography in 2016.

A Dream Job

Then, an opportunity arose to work with David Karl and the HOT team, in what she describes as her “dream job.” Lured in no small measure by the chance to be a part of what she calls “an essential ecosystem service to our planet,” White joined UH Mānoa as an associate professor in 2018. Similar to Karl, White’s work is largely conducted in the natural laboratory of the sea, with her expertise focused on ocean optics and elemental fluxes.

Through HOT, researchers have documented the variability of ocean water masses and circulation; observed habitat variability; determined relationships between microbial community structure and function, including nutrient dynamics and carbon sequestration; and measured carbon dioxide levels in the upper ocean and quantified the capacity of the ocean to absorb it.

“It’s not just a place of discovery. The important part about time series are that they provide us a sense of history, a sense of context,” said White. “And with 30-plus years of data, HOT has allowed us to separate the seasonal change and see the emergence of humanity’s fingerprints on the natural world.”

Humanities Fingerprints

Unfortunately, this has included the rapid increase of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. As CO2 levels rise in the atmosphere, CO2 also rises in the ocean, resulting in a fundamental change in the acidity of seawater. Known as ocean acidification, it has far-reaching impacts not only on the growth rates and metabolic interactions of small organisms, but also on large ecosystems like coral reefs.

“In the 33 years of the time-series, less than half the average life expectancy in the U.S., the HOT program has observed a clear and persistent increase in CO2 and the decline in pH in the top 500 meters of the water column,” said White. “What this signifies, is that the collective impact of everyday human activities from around the world has affected the water column in one of the most remote places on the planet. That should give us all a moment of pause to reflect on our actions as individuals and as a global society moving forward to curb this alarming trend. Our atmosphere and oceans have no geographic borders; they are for us all to protect.”

Not All Doom and Gloom

Along with algal blooms and ocean acidification, other issues such as sea level rise, pollution, loss of biodiversity and overfishing also pose grave threats to Earth’s delicate ecosystem. However, White is quick to point out that microbial ecosystems in the ocean are resilient.

“We know ocean ecosystems can be remarkably resilient. We just don’t know when we will have gone too far and tipped the ecological scales beyond a point of return,” said White. “Sustained observations have shed light on a changing ocean and now humanity must find a way to reverse its course and seek solutions to mitigate the rising levels of CO2 and protect the microbes that sustain us.”

A TED Talk Star is Born

In 2019, White got a chance to spread the gospel of HOT to a wider audience when she was selected as one of 14 speakers for the first science-centric TED Talk held at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. Her presentation on what ocean microbes reveal about the changing climate captured the interest of 1.8 million viewers, making it into the Top 10 most watched TED Talks of 2020 — and elevating her to “rock star” status in science.

“My short video pitch was made on the stern of a research vessel at sea with the sound of whipping winds and rolling waves drowning out most of my audio,” said White. “It must’ve made an impression on the TED folks or maybe they just felt sorry for me having to brave the elements on that pitching deck.”

The Future of HOT/Station ALOHA

“The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa is a nexus for leaders in ocean observing with extraordinary access to the sea and seagoing infrastructure,” said Brian Taylor, dean of the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST). “It is no small feat to study the largest ecosystem on the planet, yet we’ve made some amazing progress here at SOEST, which is a tribute to our researchers like Dave Karl, Roger Lukas and now Angelicque White.”

Buoyed by a five-year $9 million award from NSF in 2018, HOT will continue to maintain a vigilant watch on the ecology, physics, and chemistry of the North Pacific. The venerable program will also continue as a testbed for new technologies and experimental approaches to help solve more of the enduring mysteries of the microbial ocean, document new organisms and discover new pathways for exchange of elements and energy.

“We will continue to be leaders in open data sharing that is so fundamental for time-series and to foster curiosity, creativity, openness and a sense of connection to our natural world,” said White, who was recently promoted to full professor and is the recipient of the 2021 UH Regents’ Medal of Excellence in Research. “I am proud to lead this program forward with an incredible team at my side, and to continue the indelible legacy of the great David Karl.”