AS ONE OF THE MOST GEOGRAPHICALLY ISOLATED REGIONS IN THE WORLD, Hawai‘i residents contend with the highest electricity prices in the U.S., about double of the national average. This is due largely in part due to a heavy dependence on imported petroleum and lack of indigenous fossil fuel resources.

However, below the Hawaiian Islands lies a geological hot spot in the earth’s mantle that has been active for the past 70 million years, formed the island archipelago and today — continues to fuel Hawai‘i’s active volcanoes. Because of this hot spot and the presence of subsurface heat, the use of geothermal energy can prove to be a viable option to solve some of the state’s energy woes.

Geothermal electricity is clean, inexpensive, and firm — with the last meaning that is “always on” regardless of weather conditions or time of day. Geothermal also has the lowest land footprint compared to solar power and wind, and unlike the other intermittent resources, no battery storage is needed. Currently, the state’s lone geothermal plant on Hawai‘i Island produces five times the amount of electricity as one of the state’s largest solar farms, while requiring 80 percent less land area.

Evidence collected by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa) suggests that all of the major Hawaiian Islands may hold the subsurface heat that is necessary to produce geothermal energy. However, the current state of understanding of geothermal potential outside of Kīlauea’s East Rift Zone (KERZ), the most active rift of the state’s most active volcano on Hawai‘i Island, is very limited. KERZ is where geothermal exploration was focused in the 1970s, and is the only location in the Hawaiian archipelago where geothermal electric power is being produced.

The Hawai‘i Groundwater and Geothermal Resources Center

As Hawai‘i is the only U.S. state without a geological survey, UH Mānoa has contributed much of what is known about Hawai‘i’s geology. Since producing Hawai‘i’s first geothermal well in the 1970s, UH Mānoa has spearheaded Hawai‘i’s geothermal research, including producing the only two statewide resource assessments by Professors Donald Thomas and Nicole Lautze of the Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology in 1985 and 2017, respectively.

Realizing the need to provide a central hub from which to disseminate legacy data and information from their numerous geothermal and groundwater research projects throughout the state, Lautze and Thomas founded the Hawai‘i Groundwater and Geothermal Resources Center (HGGRC) in 2014. The HGGRC, led by Lautze, conducts research on Hawai‘i’s fresh groundwater, geothermal (including shallow geothermal heat pump technology for building cooling), and carbon storage potential. Visit: https://www.higp.hawaii.edu/hggrc/.

Hawai‘i Play Fairway Project

The Hawai‘i Play Fairway project was among HGGRC’s most important initiatives. The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa was one of eleven initial phase I projects selected and funded by the U.S. Department of Energy from across the country to identify blind hydrothermal systems (those without surface expression). The project, led by Lautze, received subsequent phase II and III funding from 2014-2020 and ultimately provided the first statewide geothermal assessment of the Hawaiian Islands since Thomas’ original report in 1985. The research project accomplished the following objectives:

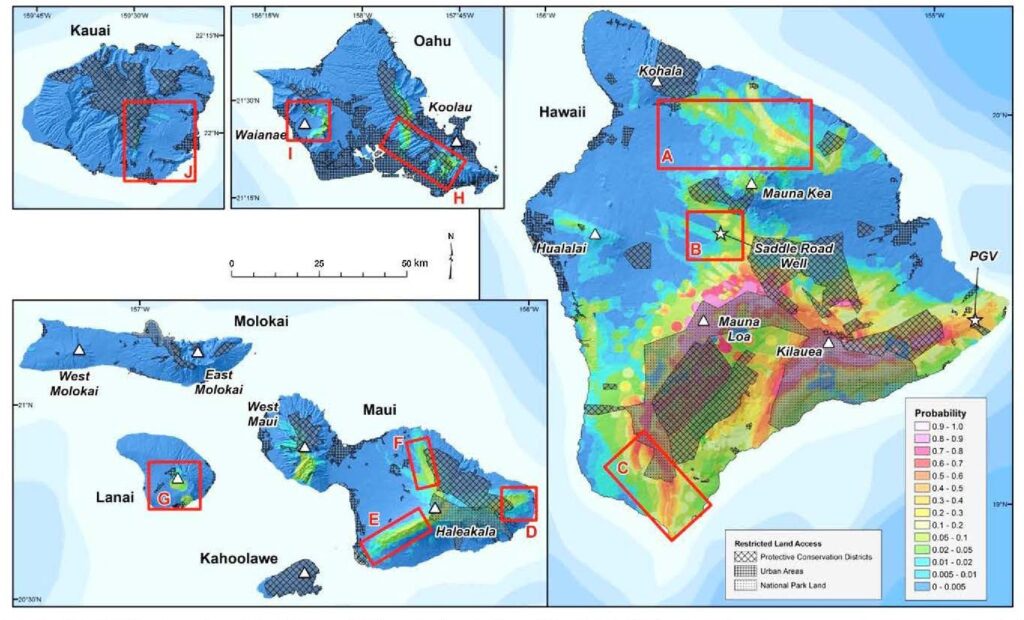

Phase I – Identified, compiled, and ranked existing geologic, groundwater, and geophysical datasets relevant to subsurface heat, fluid and permeability. Developed a statistical methodology to integrate into a statewide resource probability map. The team considered this map, confidence in the calculated resource probability, and development viability to identify 10 locations across the state for phase 2 geothermal exploration activities.

Phase II – Collected new groundwater data in 10 locations across the state, new geophysical data on three islands, and modeled topographically induced stress to better characterize subsurface permeability. Through combining data from the first and second phases, the team determined locations for exploration drilling in phase 3.

Summit of each Hawaiian shield volcano shown as a white triangle. Credit: HGGRC

Phase III – Deepened a groundwater well in Lāna‘i’s Pālāwai Basin to approximately 3,500 feet, performed more geophysical surveys, and collected limited new encouraging groundwater data. The team measured a roughly linear temperature gradient averaging 42°C/km and a maximum bottom hole temperature of 66°C, similar to some exploration wells within KERZ. This is now the deepest and warmest well off of Hawai‘i island. The team considered these results encouraging for Lāna‘i’s resource potential.

Ultimately, the Hawai‘i Play Fairway Project provided an updated statewide geothermal resource assessment, expanded understanding of Hawai‘i’s groundwater location and quality, and a roadmap for additional work to better characterize both resources. HGGRC’s philosophy is that more data will bring more knowledge, and that when this knowledge is shared with stakeholders and communities, more informed decisions can be made.

“I think nearly everyone in Hawai‘i would value a low cost, low footprint, resilient, indigenous, energy supply. But there are tradeoffs for some. If geothermal has a chance, community engagement will play a critical role,” said Lautze. “HGGRC will continue to work with stakeholders and local communities to advocate for the necessary funding to move the state one step closer to understanding and realizing its geothermal potential.”

She added, “The global geothermal community wonders why there isn’t more geothermal electricity generation in Hawai‘i. The answer is complex, but I think that if we could get even a small power plant online in a location where the local community is supportive, I think it would be transformative for our state.”