Kiana Frank, PhD

SOME PEOPLE BECOME SCIENTISTS. For Assistant Professor Kiana Frank of the Pacific Biosciences Research Center (PBRC) at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa), it was evident early on in her childhood that she was born a scientist.

As an inquisitive six-year-old growing up in Kailua, O‘ahu, Frank listened to her great grandmother’s story about the lepo ‘ai ‘ia (edible mud) in the nearby Kawainui marsh. According to the legend, the mud was eaten by King Kamehameha the Great’s warriors after the fierce Battle of Nu‘uanu, and Frank was told it to be similar in taste to her favorite food, pa‘i‘ai, (pounded taro). However, there was a catch — to gather the mud, one had to maintain absolute silence. While conducting her first silent expedition — eagerly tasting all the different colors and textures of mud in the marsh (that were not delicious) — she refined her kilo (observational skills), and developed a deep sense of ecological inquiry. While she did not find the magical mud, Frank discovered something more. Her calling as a scientist, and one who would later become one of Hawai‘i’s leading experts in environmental microbes and their role in sustaining healthy ecosystems.

“I did not become a scientist, I was born a scientist because my kupuna (ancestors) before me were natural scientists. For me, science is how I connect to and better understand the places I love. Science is my tool to mālama ‘āina (protect, care for the land).”

– Kiana Frank

One of these areas is Kawainui. Frank vividly recalls an old painting in her grandmother’s house that portrayed Kawainui not as the invasive marsh she was familiar with but as a loko i‘a (fishpond) that had once provided an abundance of food for all of Kailua. It was at that point, she began to ponder the impact of human activity on places like this. Frank delved into the foundational mo‘olelo (stories) and mele (songs) of Kailua to gain insights into a healthy Kawainui ecosystem and its historical functioning. Mo‘olelo such as the lepo ‘ai ‘ia or the Makalei (the fish-attracting branch of Kawainui) shed light on the holistic resource management practices employed by ancient caretakers who recognized the interconnectedness of upland and near-shore ecosystems. However, they also served as powerful reminders of the potential consequences of inadequate stewardship, with poignant warnings that neglecting the care of Kawainui could result in the transformation of its waters into land.

“Our kupuna laid the groundwork with their scientific discoveries and passed on their knowledge to us in their mo‘olelo,” said Frank. “It is our responsibility to learn from their observations and to continue to tell their stories.”

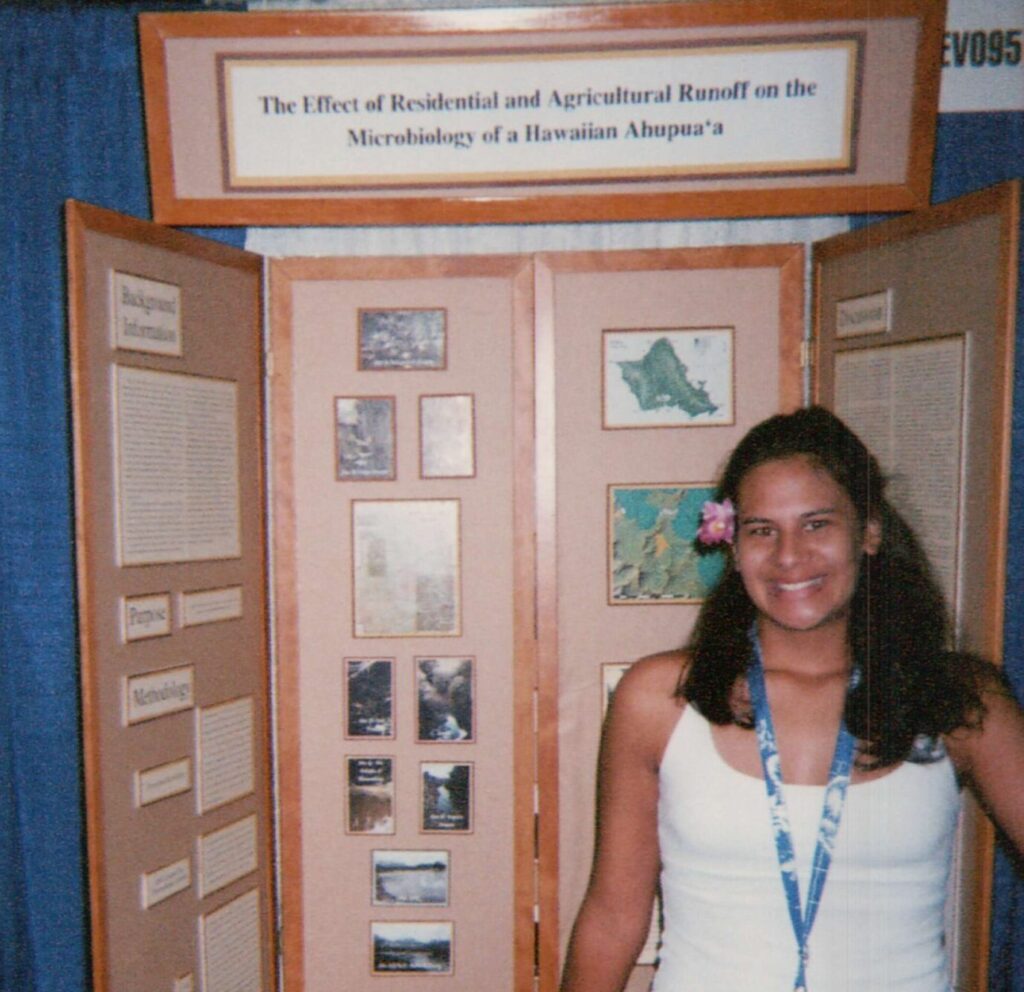

As a freshman at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama, Frank discovered the magnificent world of microorganisms. Microbes — the most abundant and diverse tiny organisms — hold immense power in shaping our ecosystems. They form the foundation of the food web, influencing the availability of nutrients and carbon for other organisms like algae, zooplankton, and fish. Frank believed that understanding the role of microbes in the ecosystem was crucial to restoring the productivity back to lo‘i (taro patch) and loko i‘a, as well as the key to finding the lepo ‘ai in Kawainui. So, she began to collect samples of microbes across Ko‘olaupoko investigating how land management influenced the diversity and distribution of microorganisms across ahupua‘a (traditional unit of land management that runs from mountain to sea). She eventually developed a novel technique for DNA extraction from small volumes of water so she did not have to hike up and down mountains with gallons of water. For her ingenuity and innovative work that was a part of her high school science project, she earned first place and best-in-category in environmental sciences at the 2004 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Portland, Oregon.

After graduating, Frank earned a full merit scholarship to the University of Rochester where she studied molecular genetics and earned her Bachelor of Science degree magna cum laude in 2008. She continued on to Cambridge, Massachusetts to pursue research at the intersection of microbial ecology and biogeochemistry under Professor Peter Girguis — earning her Master of Arts and PhD in molecular cell biology at Harvard University in 2010 and 2013, respectively. When she returned home to the islands, her childhood dream of becoming a professor at the UH Mānoa was realized.

Today, Frank uses modern techniques in microbiology, molecular biology and geochemistry to complement and expand upon the observations of her kupuna. With a unique blend of storytelling and scientific rigor, she brings to light the intricate workings of the world. From the tiniest microorganisms to the vastness of nature, Frank unravels mysteries of the unseen to deepen humankind’s understanding of and relationship to place.

“The deep held pilina (relationship) between ‘āina (the land), akua (natural elements, spiritual deities), and kānaka (the people) provided the foundation for ancient Hawai‘i’s thriving abundance. Microbes are the physiological representations of this pilina.” said Frank. “Microbes are our akua, they are the unseen mediators of geochemical processes and ecosystem services that shape productivity ma uka i kai (from the mountain to the sea).”

Reminiscent of her childhood days, a majority of Frank’s work at PBRC takes her into the field, working side by side with local communities, to collect mud and water samples. Integrating contemporary scientific techniques with ‘ike kupuna (traditional knowledge), Frank decodes the reasons behind traditional management practices and constrains of biogeochemical cycling associated with agriculture and aquaculture production. She recognizes that her ancestors, although unable to physically see microorganisms, possessed a deep understanding of their existence. This understanding is evident in many traditional management techniques, such as how the development of auwai (continuous flow irrigation) and act of hehihehi (stomping) oxygenates lo‘i to prevent root rot caused by anaerobic microbes; or how the planting of hau (Hibiscus) around loko i‘a serves as a biological indicator of microbial nitrogen cycling, signaling the need to adjust the mixing of water. Her lab also monitors the diversity and distribution of microbial communities along ahupua‘a to assess health risks associated with aquatic pathogens — highlighting the profound effects that modern development, industrial agricultural and climate change have on ecosystem function. Frank’s data helps to support informed decision-making, effective management, and impactful policies for long-term social-ecological resilience.

“Ecosystem sustainability was not just a concept of our kūpuna, it was their daily practice,” said Frank. “They used conscientious management strategies based on strong kilo to create sustainable and manageable systems to feed people. We need to move back to that — i ka wā ma mua ka wā ma hope (moving forward into the future with your eyes to the past). Ancestral Hawaiian management practices are the models that we need to emulate as a foundation for contemporary innovation in response to climate change.”

Helping to accomplish that is a summer Research Experiences Undergraduates (REU) program for Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) college students that Frank co-runs with Assistant Professor Matt Medeiros and is funded by the National Science Foundation. The objective of the 10-week REU program hosted by UH Mānoa is to cultivate a cohort of NHPI students who receive comprehensive training in scientific research and engagement of indigenous communities, particularly in disciplines important to their islands’ future, such as ecology, environmental biology, and conservation science. These students work alongside multidisciplinary faculty mentors from UH and members of Kauluakalana, a non-profit community based organization working out of the Ulupō Heiau — dedicated to the ecosystem restoration of Kailua through culturally informed protocols and Hawaiian ways of knowing.

“Through Kiana’s work and teachings, our young scientists are able to pair what we know from our kupuna with what we know today from her study of microbes to help revive this area,” said Kaleo Wong, executive director of Kauluakalana.

Frank’s work is driven by her commitment to fostering inclusive spaces for transdisciplinary research, honoring indigenous knowledge, and embracing ancestral practices for contemporary innovation. By nurturing a deep connection to the land and collaborating with ‘āina-based community organizations and stakeholders, she ensures that her research is rooted in the values and principles of traditional management. Through her exploration of the intricate world of microbes, Frank unveils a hidden realm of immense significance, shedding light on the profound influence of these microorganisms in shaping the environment. Her findings not only expand humankind’s knowledge, but also hold the potential to unlock innovative solutions for pressing global issues. By perpetuating place-based knowledge and ecological-based studies, she paves the way for a future where science and tradition intertwine to sustain and protect the natural world — a future where fish have returned to Kawainui loko i‘a, and a little Kailua girl can savor the delightful taste of the lepo ‘ai ‘ia.